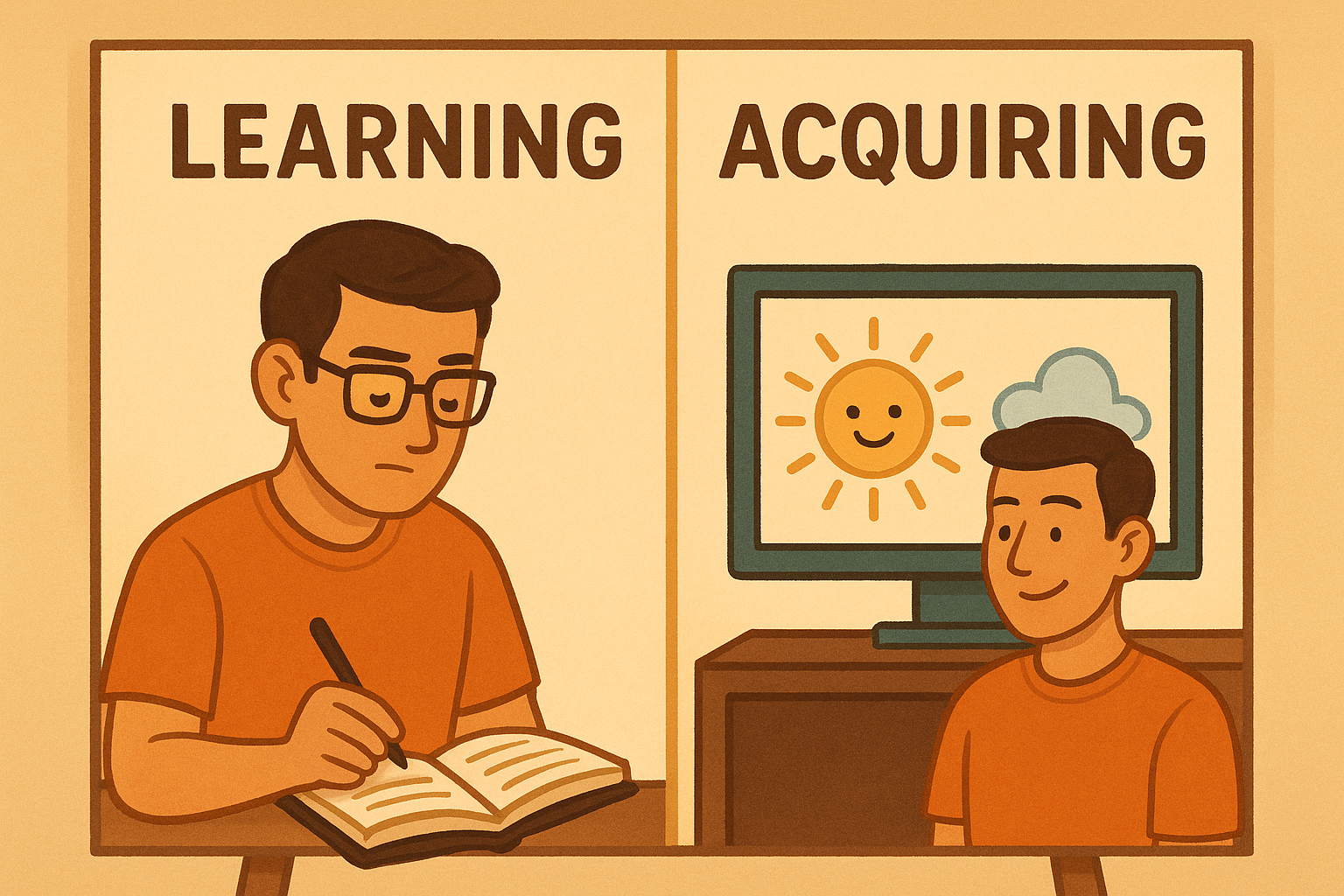

What’s the difference between learning and acquiring a language?

If you’ve ever memorized vocabulary lists, crammed for grammar tests, or stared blankly at a textbook, you’ve been “learning.”

But if you’ve ever just understood something without effort—picked up a word just by hearing it a few times you’ve been acquiring.

Comprehensible Input is all about the second one.

Learning Is Conscious. Acquisition Is Subconscious.

Dr. Stephen Krashen, the guy behind the Comprehensible Input hypothesis, says language comes into your brain in two ways:

- Learning is the stuff you do in school. Study grammar rules, memorize charts, take quizzes. You know about the language.

- Acquisition happens when you understand messages. You don’t think about conjugations or word order. You just get it.

Krashen says real fluency comes from acquisition, not study. You don’t need to learn the rules before you can speak. You can absorb the language by hearing and understanding it, just like you did when you were a kid.

Why “Learning” Doesn’t Stick

The school system loves learning. It’s measurable. You can be tested on it.

But most of us forget what we crammed the second the exam is over.

How many times have you said, “I used to know this,” but couldn’t remember how to say anything in a language you studied for years?

That’s because you learned it, but didn’t acquire it.

Learned knowledge is stored in the academic part of your brain. It’s slow, clunky, and easy to forget.

Acquired knowledge lives in your subconscious. It’s fast, automatic, and sticks.

What Acquisition Feels Like

Let’s say you’re watching a Dreaming Spanish video.

Pablo draws a cat. He says:

“Un gato… duerme… MUY bien… zzzzz…”

And mimes sleeping.

You don’t need a grammar explanation. You get it.

You see the image. You hear the word. You feel the meaning.

That’s acquisition. You didn’t memorize “duerme = sleeps.” You experienced it.

Can You Learn and Acquire at the Same Time?

Kind of.

You can learn a grammar rule and notice it in context later. But for it to stick, and for you to use it naturally, it still has to be acquired.

Krashen believes that learned knowledge can only help with monitoring speech. Like double-checking what you’re about to say. It doesn’t create fluency.

That’s why even after years of grammar drills, many learners still freeze when trying to speak.

Acquisition is what makes the words come out naturally, without thinking.

CI Learners Focus on What Matters

The CI approach doesn’t ignore learning. But it doesn’t start with it.

It starts with understanding.

You watch, listen, and read content that’s just right for your level. What Krashen calls i+1. It’s mostly understandable, with a few new bits that you can figure out from context.

No pressure. No drills. No speaking before you’re ready.

Eventually, things start to click. Words you’ve heard 20 times finally stick. You find yourself understanding entire sentences you didn’t even realize you knew.

That’s the magic of acquisition.

Final Thoughts. Trust the Process.

If you feel like you’re not “doing enough” because you’re not studying grammar or doing flashcards, stop.

You’re doing what works.

Understanding messages is the work.

Comprehensible input is how you acquired your first language. It’s how you’ll acquire the next one, too.